Bake-a-Day Sourdough

Welcome to another step-by-step recipe from BreadClub20. Why not drop by our main Facebook page by clicking here.... If you like what you see and enjoy the recipe, we hope you go on to join us by 'Liking' and 'Subscribing'.

I'm on a recruitment drive - to try and persuade all those of you for whom sourdough looks cumbersome, time-consuming and feel it needs to be planned like a military exercise, that it's actually not. Not at all.

I've baked sourdough for years and I've baked yeasted breads for decades. Lately, I've been on a 'bit of a mission' to remove the mystique of sourdough to enable every home baker to produce tasty sourdough with the minimum of fuss and equipment; but with the maximum taste and all within everybody's daily schedule.

Daily Schedules! They are the masters of our lives. We may have jobs to go to, families to look after, places to be...how do we fit in producing wholesome sourdough bread within schedules and routines that run our lives and eat into our spare time?

Let's start with a few personal 'gripes'. As a new baker, the temptation is to buy armfuls of books on sourdough baking. They're often beautifully written and very glossy. However, what one often finds is that they all cover the same ground:

1. Here's a stack of equipment you need to buy. Really? I don't think so!

2. Here's a lot of techniques you need to employ. Really? I don't think so!

3. Here's a whole range of recipes that are all variations on a theme and most of them you'll probably never bake; all designed in commercial kitchens at varying temperatures in places all over the World. Really? I don't want / need them.

But there are some truths in this...for the future when you're on your own Sourdough Journey...

1. Yes, you will gather equipment and, as you progress and develop your craft, you'll want to acquire some specialist pieces. But that's for the future.

2. Yes, there are a lot of techniques - but, those are also for the future.

3. Yes there are many YouTube videos, courses, teaching texts and tomes and countless sourdough books...but that's for the future.

3. What you really want now is a good-looking - good-tasting loaf, over and over again and trust and belief in your own skills that when you bake, the end product will deliver just what you wanted, time and time again.

There are many Facebook groups that support sourdough baking. For the beginner, I'd advise a group where not everybody is a beginner. I'd advise a group where people are genuinely willing and able to provide advice that will move you forward and not simply to tell you it's good so as not to offend. I often call these 'self-adulation groups'.

To be honest, that's why I set up BreadClub20. I wanted somewhere where people could learn through both their successes and their failures. A virtual classroom for all of us, because, believe me, even after decades of baking, every day is still a learning day. It's not just a sourdough group, however. It covers all manner of breads, yeasted and sourdough, local, regional and international.

If you want a free guide to a first sourdough that will save you buying a whole shelf load of unnecessary books, subscribe to BreadClub20 and drop me a line at breadclub20@gmail.com. I'd be happy to email you a copy.

Take a tip - read one book and read it thoroughly. I'd recommend John Carroll's 'Sourdough Made Easy' (ASIN : B01K31815O). It'll give you the only three recipes you'll need for quite a while.

FORMULA AND PROCESS

I rarely use the term 'recipe'. Sourdough isn't a 'recipe', it's a formula. There are only four variables.

1. Flour - I use a strong bread flour with a relatively high protein percentage (usually it's listed on the pack somewhere) of somewhere between 11.5% and 14%. I may use strong white in combination with brown bread flour, spelt flour, rye flour and wholewheat flour. But, take it from me, if this is your first sourdough - stick to strong white bread flour. When you've mastered that, move on.

2. Water - If you live anywhere where you can drink the tap water without grimacing, it's fine. If it's heavily chlorinated, leave it a while to allow the chlorine to escape. If you're unsure, use filtered water or the cheapest bottled water you can buy. If you have spring water, you are amongst the blessed.

3. Salt - I always avoid iodised salt, for everything. I use a sea salt - it's my preference.

4. A levain / starter / fermentation / inoculation / culture - you'll find it called so many things. It's simply a prepared mixture of any flour and water that has fermented over time and has active bacteria within. BreadClub20 has a easy guide to producing your own starter HERE.

Beware the myths about 'starters'. While you're buying your books and reading your way into confusion, you'll come across all manner of sourdough techniques - some are very valid and have a real purpose, others are of little help, to be frank.

1. The 'float test' is unnecessary, a poor guide and too often advocated by those who have not got beyond an early stage in their baking of bread.

2. Feeding your starter at a precise time is a risk. In a warm kitchen it will reach its peak earlier than it will in a cool kitchen. Just watch the dough, not the clock. It will rise, stay risen and fall back. The optimum time to use it is while it's at the 'stay risen' stage. But, even when it's falling back, it'll be good to go. I feed mine before bed and it sits in my 17⁰C kitchen for 8 / 10 hours and it's usually ready for the morning. However, if I use the hot water cylinder cupboard upstairs (24⁰C) it's ready in 3 / 4 hours.

3. You don't need a lot of starter. My Bake-a-Day formula requires 50 gms. I tend to make a little more so I can keep some back to be fed next time. So I take 50 gms starter and mix it with 50 gms of flour and 50 gms water (Total 150 gms). I use 50 gms so I have 100 gms left. Next time, I'll take 30 gms out and mix that 1;1:1 again. Slowly, I use my starter until I haven't got very much and then I make more than I need to replenish it. At any one time, I only have 50 - 100 gms in the refrigerator.

4, You can use a little starter or a lot. here are my basic rules:

A little starter produces a longer fermentation and a stronger taste.

A lot of starter produces a quicker fermentation and a less strong taste.

A warmer kitchen will produce a quicker fermentation than a cooler one.

Those are the only rules you need. By a little starter, I mean about 5% - 10% starter against volume of flour. By a lot of starter, I mean 15% - 20%.

5. If you bake every day, wash out your old starter and fill your starter jar with what's left fro the refeed. Keep it on your worktop. If you don;t bake every day, you might want to keep it somewhere cool or in the refrigerator. Keep it healthy, though, it's a living thing.

And that's the formula. Whether you're making one loaf or five hundred, the formula is the same. Everything in grams.

TIP : WEIGH, DON'T MEASURE.

Let's refer to the total flour as = 100%

Water - I'd suggest 70% of the weight of the flour. When you start off, this is a safe hydration. When you become adventurous, you can move up from this percentage

Salt - I'd recommend 2% of the weight of the flour

Starter - I'm working on 10% for my 'starter loaf'. It's a safe amount.

You might read about Baker's Percentages - that's it, it's as simple as that.

And temperature? Well, my kitchen is 18⁰C most days. If you're working at higher temperatures, you'll be through the process more quickly. if it's very cold in your kitchen, it'll take a lot longer.

You'll read a lot about proofing boxes and ovens with the light on / off. This is just creating an artificial environment because you want to slow down or speed up the process. In the winter, I use the hot water cylinder cupboard at home that is 24⁰C otherwise I'd be waiting around for a lot longer than I want.

PROCESS

This is where many new bakers come adrift. This is where it's easy to become bogged down in terminology and technique and where you'll find a thousand opinions, many conflicting.

Sourdough can be broken down to three stages:

MIX - Here you add your water to your flour to your salt to your starter and mix it all together.

Until you are confident in what you are doing and have baked many successful loaves, you really don't need to worry about autolysing, bassinage, delayed inoculation of starter, Those are for the future, if ever.

WAIT - Here you are giving the gluten time to develop. It's often called Bulk Fermentation. Bulk Fermentation is a combination of first stage fermentation (in the kitchen) and second stage fermentation (in the refrigerator). We help it along a little by working the dough. This is not a fine science. Simply give it a little attention over the next three or four hours. The easiest method is 'stretch and fold' - well, the stretch is more important than the fold, to be honest. Pick the dough up, pull it gently towards you and fold it back. Keep moving around the dough until it's all had a workout. And that's it. Three or four times over the next few hours is all it needs.

Once the dough has risen to where you want it to be, it needs to be popped into the refrigerator for a while to develop taste. As little as 3 hours is fine but it can be a lot longer - 12, 16, 24 hours....it's there where you want it to be until you have the time to bake it.

You can transfer the dough to the refrigerator as it is and then shape and bake it afterwards. Or you can shape it before transferring it to the refrigerator and bake it when you are ready.The choice is yours.

When do I transfer it to the refrigerator?

You transfer it to the refrigerator when it has bulk fermented for long enough. There are schools of thought that talk about dough 'doubling' and others that talk of a 50% increase, or a 70% increase.

Let's try to find a happy medium.

In the first instance, I'd recommend finding a bowl that helps you along this road a little.

For the formula below, I'm using a bowl that is 23cm x 11 cm - it's a similar one to that recommended by the Sourdough Whisperer, Elaine Boddy. It's made by Duralex in France and readily available on Ebay. Why use this? Because it holds exactly 2 litres of water. When my formula (see below) expands to fill it, I know that it's fermented to where I want it to be.

So, as an alternative, you can find any large bowl in your kitchen, pour in two litres of water and then mark the level with an indelible pen or a piece of tape. That's the level you need. Once the dough has expanded to that, it's time for the refrigerator.

You can cover your bowl with a plate or a board or even a shower cap. A cover stops the dough drying out and keeps the bugs at bay.

Until you are confident in what you are doing and have baked many successful loaves, you really don't need to worry about lamination, slap and fold or coil fold. Those are for the future, and you will eventually take them on board.

Later on in your break baking journey, you'll hear about stopping your fermentation at 50%, 70% etc. That's the time to start investigating why - you'll already have a large number of successful bakes under your belt at 70% hydration.

BAKE - You'll need to decide whether you want to shape your dough now or later. It's your choice.

If you don't want to shape it now, place the dough in the bowl, covered in the refrigerator. It will now continue to proof...very slowly...and be ready when you are.

Cold proofing does not STOP the fermentation, it RETARDS it. It slows it down and helps to develop taste. The longer you leave it at this stage, the more sour the sourdough.

If you want to shape it now - before you place it in the refrigerator, then carry out the next procedure.

Either way, the key word here is gently.

Gently tip the dough out onto a floured surface. You'll find it very sticky. Rice flour or semolina flour are fabulously non-stick. Buy some. Gently bring the dough together into a ball by gently bringing in the edges to the middle and then turning the dough over so that the smooth surface is at the top. Gently draw the down towards you to help develop a skin on the surface of the dough.

You can cold proof in anything as long as it's well floured with a good non-stick flour like rice flour or semolina flour. A bowl lined with a tea towel is excellent. Or you can buy a banneton. They'll last a lifetime. Buy a wicker one. Be careful of Bakery Accessory shop prices or places recommended by authors in books who may (or may not) be on a commission. Direct from a Chinese source via Ebay is often far, far cheaper.

Now, if your dough has already been in the refrigerator, it's ready for baking. If it hasn't, it's ready for the refrigerator. Cover it and pop it in for as long as you need (see above).

You'll read about baking on pizza stones, under cloches, in enamel roasters, in expensive Dutch Ovens and on steel baking sheets. Take a tip - buy a cheap enamel roaster with a lid and use that until you're really bitten by the Sourdough Bug. Then treat yourself. And, until then, forget about misting, ice cubes, lava rocks, self-steaming ovens - those are for the future, if ever. The roaster does all that in one little tin box.

Until you are confident in what you are doing and have baked many successful loaves, you really don't need to worry about poke tests and the like. Just follow the process and you'll be fine.

Cheap : enamel roaster / baking steel or tray with a metal bowl inverted as a cover

Middle of the road : pizza stone / terracotta cloche

Expensive : Dutch Oven / Metal cloche / 'Challenger' pans

Some people have ovens that bake at volcanic temperatures. Some wish they did have. I have a simple rule:

Bake for 30 minutes with the lid on at 240⁰C and for 20 minutes with the lid off at 230⁰C. But I watch the dough, not the clock. It might need less, it might need more. It'll be the right colour, the right smell and nice and hollow when you tap it. It's done!

Until you are confident in what you are doing and have baked many successful loaves, you really don't need to worry about thermometers - the bread will look done. Just let it cool until cold before you cut it. The crumb is different than that of a yeasted loaf - it needs to 'set'.

The biggest issue I find is that bakers want to run before they can walk. Enthusiasm takes over. Be careful. The Baking Journey is a road full of pot-holes and ruts. Take your time. Walk slowly and steadily and you'll find the road a good deal easier and more pleasant.

So, let's try and fit this formula and process into a routine.

BUILDING YOUR ROUTINE.

ROUTINE ONE - EARLY MORNING START

Night before - feed starter

Morning (before breakfast) - mix ingredients. Work the dough occasionally between then and lunch time.

Afternoon - let the dough expand

Late afternoon, early evening - when the dough is ready, shape and put it into the refrigerator if you want less work the next day. Or put it in the refrigerator because you've got the time to shape and bake on the next day.

Next morning or afternoon or evening - Bake.

That evening - feed starter for the next bake.

ROUTINE TWO - AFTER WORK START

Breakfast - feed starter before going out.

Early evening - mix ingredients. Work the dough occasionally between then and bed time. Leave the dough out on the worktop (make sure it's not too hot in the kitchen) overnight.

Early morning - shape the dough and place in the refrigerator. Feed the starter for the next bake.

That evening - bake the bread and mix the ingredients for the next bake and work the dough between then and bed time.

I hope you can see that you can quickly develop a pattern that will produce you a daily loaf.

if you're producing too much bread for yourself :

a) give a loaf away every so often

b) pop a loaf into the freezer for 'emergencies'

c) miss a day and simply hold the starter between feeds by popping it into the refrigerator

d) miss a day by delaying the baking of a loaf by 24 hours or so.

OK - Let's start the Bake-a-day Sourdough.

Starting time. Let's set the clock.

Sometime around the hour mark, work the dough a little by wetting your hands, lifting it from the bowl and pulling it upwards towards you and letting it flop back into the bowl. Keep doing this until all the dough has had a bit of a workout. Each pull is likely to cover a quarter of the dough, so four times is ideal. It shouldn't take you more than 20 seconds.

It's time now to let the dough have some peace and quiet and give it time to expand. Cover the bowl and let it rest to ferment.

|

| Almost there.....another 30 - 45 minutes and we'll be ready for the shaping and cold proofing. |

|

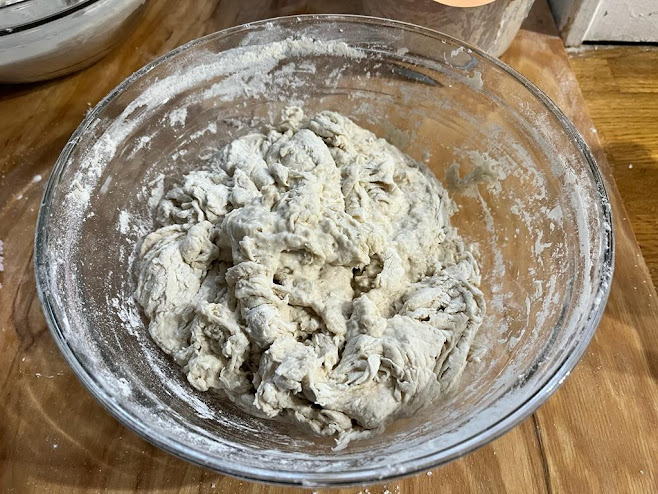

| Ready to shape |

|

| and into a banneton. |

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

I have a couple of questions: (1) What would be the effect on the process of using a recently fed and very healthy but not currently active starter - i.e., cold from the fridge? (e.g., bulk fermentation might take longer?) or, alternatively, (2) Would it work to measure out, e.g., 10 g starter, 20 g flour, 20 g water, into my mixing bowl, and when it reaches maximum activation then carry on with mixing and the rest of the process?

ReplyDelete