Simply Sourdough - BC20 style (Easy Difficulty)

Today is all about Simply Sourdough...not 'Simple Sourdough'. Although sourdough is 'simple' in terms of its formula, it takes a bit of practice, knowledge and understanding before you have one of those 'Eureka' moments and you begin to understand how all the facets of sourdough baking integrate and make sense.

There are three types of sourdough bakers: those who know exactly what they're doing, those who haven't a clue and those who are somewhere in between.

This is really aimed at those who are just starting out on their sourdough journey or who have been baking sourdough by following, with almost religious zeal, word-by-word instructions from one of the many, many books on sourdough baking.

Have you noticed that so many sourdough cookbooks are practically the same? The first half of so many of them tells you yet again about the equipment you already have. The second half gives you a basic recipe and presents you with too many recipes for bread you'll never bake?

You'll be drawn into a world where people will purport to have discovered the master recipe; where they will persuade you that their way is the only way.

Sourdough is probably the oldest bread in the world. It's possibly the first manufactured product. Somewhere, sometime, someone first experimented with grinding grain, mixing it with water and leaving it to ferment before placing it in or on the first and turning it into bread. Flatbread became fermented bread became sourdough.

Sadly, sourdough instruction and advice in print and on the web has become full of snake-oil salesmen, abracadabra conjury and, quite honestly, a fair sprinkling of hogwash.

You won't read here about the necessity of window pane tests, the compulsory finger tests and the like..I'll leave those to people like this that seem to pop up everywhere on social media. :

Today, I'm going back to basics.

SimplySimple Sourdough.

This is one of a series of bakes that I've called...

It's a simple idea. If you're an inexperienced baker, then here's a recipe for you for the first time you bake a straightforward sourdough. Then, bake it again, and again and again...until you understand the formula and understand the processes.

After that, adopt the formula, adapt the ingredients and the processes and improve the end product. That's the challenge!

That's what being a good home baker is all about.

As we know, simple straightforward sourdough is made up of four ingredients:

FLOUR - Today, we're using strong white flour (about 13% by protein). However, when you're adapting this formula, you could use wholemeal, brown flour, spelt, rye (as you become more proficient). In fact, any flours in combination. But, to start out, I'd recommend white.

WATER - Use filtered or bottled. If you live in a hard water area or if your water is heavily chlorinated, believe me, filtered or bottled water will make your bread taste better. If you live in a soft water area, or in the middle of nowhere....then rainwater or tap water will be fine.

We're going to talk later on about hydration levels.

If you're not sure about hydration levels in sourdough, click here:

https://breadclub20.blogspot.com/2020/10/a-very-simple-guide-to-hydration-levels.html

SALT - avoid iodised salt at all costs. I use crushed sea salt....smoked salt is a nice alternative.

STARTER - or 'levain' as it's sometimes known. This is the combination of fermented flour and water. over time it builds up the bacteria you need to ferment your bread and turn it into sourdough.

If you need to build your own starter - click here:

https://breadclub20.blogspot.com/2020/11/making-your-own-sourdough-starter.html

Building the formula:

1. Flour - we're going to need 500 gms of strong white flour (or in combination, see above)

2. Water - I want this sourdough loaf to be 70% hydrated. (see above for an article on hydration). To do this we need 70% of the weight of the flour to be water. This is called Baker's Percentages. If you're not sure about what I mean by Baker's percentages, click here...

https://breadclub20.blogspot.com/2021/03/de-mystifying-bakers-percentages.html

So, we're going to need 70% of 500 (flour) which is 350 gms of water.

3. Salt - we're going to need 2% salt. (2% of 500 = 10 gms)

4. Starter - about 4 / 5 hours before you start to bake, feed some of your starter with fresh flour and water. I leave it somewhere warm (about 21⁰C - 24⁰C).

I usually take 100 gms of starter and add 100 gms of tepid water and 100 gms of 'bench flour'. (Bench flour is the flour that I've gathered up from my workbench and saved from my bakes. It's usually a combination of all the flours I use: strong white, brown, wholemeal, T55, Tipo 00, spelt, rye, etc. Why waste it?

Look how straightforward this is:

Think about the quantity of starter in relation to time and temperature.

In your kitchen:

Is it warm? Then use less...

Is it cold? Then use more...

Is it winter? Then use more...

Is it summer? Then use less...

Are you in a hurry? Then use more...

Have you lots of time? Then use less...

It's more or less as straightforward as that. Those are your variables.

Today, we're going to use 12% starter. Why? Because it's pretty much a middle-of-the-road amount.

In winter I'd use 15% and in summer I'd use 10%.

If I start late for some reason, I'd use 15%. If I got up early and got organised, I'd use 10%

12% starter is 12% of my total flour = 60 gms.

You'll have read that I made 300 gms of starter. That's because I'm using 60 gms for each loaf. If I bake three loaves at a time, that 180 gms of starter.

What's left over will go back in the refrigerator for next time.

So, let's look at my formula,

500 gms of strong white bread flour

350 gms of tepid water

10 gms crushed sea salt

60 gms of recently fed, active starter.

And that's it. It's as straightforward as that.

Now, we need to think about the process.

1. Take a large bowl. Add the water and then the starter. Swish it around a bit and then add the flour.

2. Stir it all together, cover it and place it somewhere warm for an hour.

This is called autolysing...it's not essential, but it does allow the flour to settle down into the liquid and start to slowly amalgamate.

When I say 'warm place' - my kitchen in 19⁰C and my cupboard upstairs is 24⁰C.

The 24⁰C cupboard is absolutely perfect for sourdough fermentation....see how close you can get to that.

3. Now stir in the salt and mix it all together.

That's the end of the first stage. The next stage takes a little time.

Over the next two or three hours, we're going to spend a few minutes every so often giving the dough a stretch to help build gluten. Really, we simply pull one side of the dough and lay it over itself, then repeat this on all four sides. It's as simple as that. A wet hand helps - the dough doesn't stick to a wet hand.

We call this 'stretch and fold'. It's a basic sourdough process.

We're going to do this three times at 45-minute intervals. Straightforward as that.

You can Google YouTube videos on 'coil folding' and 'laminating', if you wish. These are techniques that add variety - for when you've baked this a few times and are ready to adapt and adopt new processes. They're not necessary, just new skills on the sourdough journey.

4. Stretch and fold #1

5. Stretch and fold #2

6. Stretch and fold #3

7. Now, we need to leave the dough somewhere warm to bulk ferment. That means to grow to a point where we know it's grown enough

The Sorcery of Sourdough will tell you to let the dough double in volume, even triple in volume.

No!

The dough contains bacteria and life. We don't want to exhaust it into premature death. We need it to have enough energy to take us right to the very end.

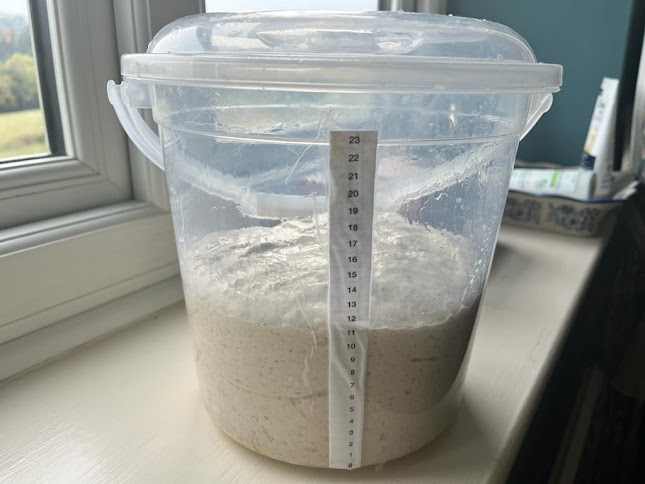

If you can find a container with straight sides....maybe a large ice cream container, or a small food-grade bucket, find a ruler and measure out and mark the side in incremental distances.

Oil the container and transfer your dough into it. Note the volume and then work out where it needs to come to it it is to increase by 80%.

If it's very warm, note where 70% increase would be.

If it's not very warm at all...80% is fine.

As you become more proficient, you can experiment with 60% or even 50% increase by volume.

On the graduated scale pasted on the side of my bucket (it's an Excel column and fixed with good-quality sticky tape), my dough comes up to '11'. 100% would be '22', therefore. 80% expansion would be 17.6...call it 18.

And now, we wait. We watch the dough, not the clock and we watch and wait....until it's increased to the 80% mark, ie. '18' on my scale.

8. Very gently (to protect all those lovely air bubbles), we tip the dough out onto a floured board. Buy yourself some rice flour. It makes life a lot easier, believe me.

9. Gently form the dough into a ball. gently draw it around the worktop, helping to build up tension on the surface of the dough. Cover it and let it rest for 15 minutes.

11. Now you're going to need a baking vessel.

Dutch Oven - a cast iron casserole or oven-proof casserole dish with a lid

Enamel Roaster

Pyrex glass lidded casserole

Pizza stone and a metal bowl that can be used as a 'lid' or cover

Baking sheet and metal tray that can be filled with water to create steam.

Covered vessels create their own micro-climates and therefore their own steam.

Uncovered sheets or stones need the added benefits of steam to help the dough rise.

12. Preheat your oven to 240⁰C (or thereabouts). Also preheat your baking vessel.

You'll read about cold and hot starts - that's for another day - when you're starting to adapt the process based on experience. Do some homework in the meantime.

13. Take the dough out of the refrigerator and invert it onto a piece of parchment paper or a silicone sling. Both work equally well.

14. Take a sharp knife or razor blade and slit the dough to allow the pressure to be released as it's cooking and for the dough to expand.

15. Place the dough into the hot baking vessel, cover and bake for 30 minutes at 240⁰C or thereabouts.

16. After 30 minutes, take the lid off, drop the temperature down by 10⁰C and Continue to bake until the loaf is golden brown and hollow when tapped on the underneath (about 15 - 30 mins extra).

17. Cool on a rack for AT LEAST two hours, preferably more. The sourdough crumb needs to set.

And that's it.

It's as straightforward as that.

When it's cooled, cut it open and admire your handiwork.

OK, I've adopted this formula...how do I adapt it and improve it.?

To adapt it?

Change the flour combination.

Change for water for kefir

Change the quantity of the starter or even the style of starter. A rye starter? A fruit water starter?

Change the salt. What about smoked salt? Lo-salt?

Change the variables. Cold start? Open bake? Bake as an oval? Shape into baguettes, rolls, etc?

Add some ingredients? Chillies, nuts, seeds, spices?

Does this improve it?

Well, that's for you to do and for you to find out....who needs a book for this? You'll understand the formula and the process. The rest is in your head and at the tips of your fingers.

Well, you've baked it over and over again, and you're beginning to understand that sometimes you may be disappointed and, at other times, you'll be elated. Even the very best baker, the most experienced baker can have a bad day.

You'll also be asking questions.

How do I get a more open crumb?

What happens if I vary the way I develop gluten?

What's the science of sourdough?

What would happen if I baked it in a different way?

What happens if I change the flour, the liquid, the salt, and the starter?

You've arrived....now there's time for Google, YouTube and some advanced books on sourdough. Money is better spent there than on the rudimentary books that are of limited use.

Happy baking...

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment